The story of denim is often simplified, but its history is a complex tapestry woven from Italian utility, French ingenuity, and American innovation that created a global symbol.

Summary

- Denim’s history begins in Europe with distinct fabrics from Genoa (jean) and Nîmes (denim), which were fused in 1873 when Levi Strauss and Jacob Davis patented riveted work pants to meet the demands of the American West.

- Once purely utilitarian, blue jeans evolved into powerful symbols of identity, adopted first by cowboys and 1950s rebels, and later by the Civil Rights Movement as a uniform of solidarity and the hippie counter-culture as a statement of individuality.

- In the late 20th century, the working-class staple was transformed into a high-fashion status symbol through designer branding and industrialized finishing techniques like stone washing, which manufactured the “authentic” worn-in look.

The blue jean is arguably the most significant garment of the modern era. It’s a universal language, worn by presidents and protestors, rock stars and ranchers. It has walked the dusty roads of the Gold Rush, taken center stage at Woodstock, and graced the runways of Paris. Yet, the story of this global icon is often simplified, masking a complex history that begins not in the American West, but in the textile mills of Renaissance Europe. The very words we use—”denim” and “jeans”—are often used interchangeably, but they reveal two distinct textile traditions woven together by American ingenuity.

The Tale of Two Cities: Genoa and Nîmes

The roots of the blue jean lie in two different European cities, each producing a distinct fabric that would eventually converge.

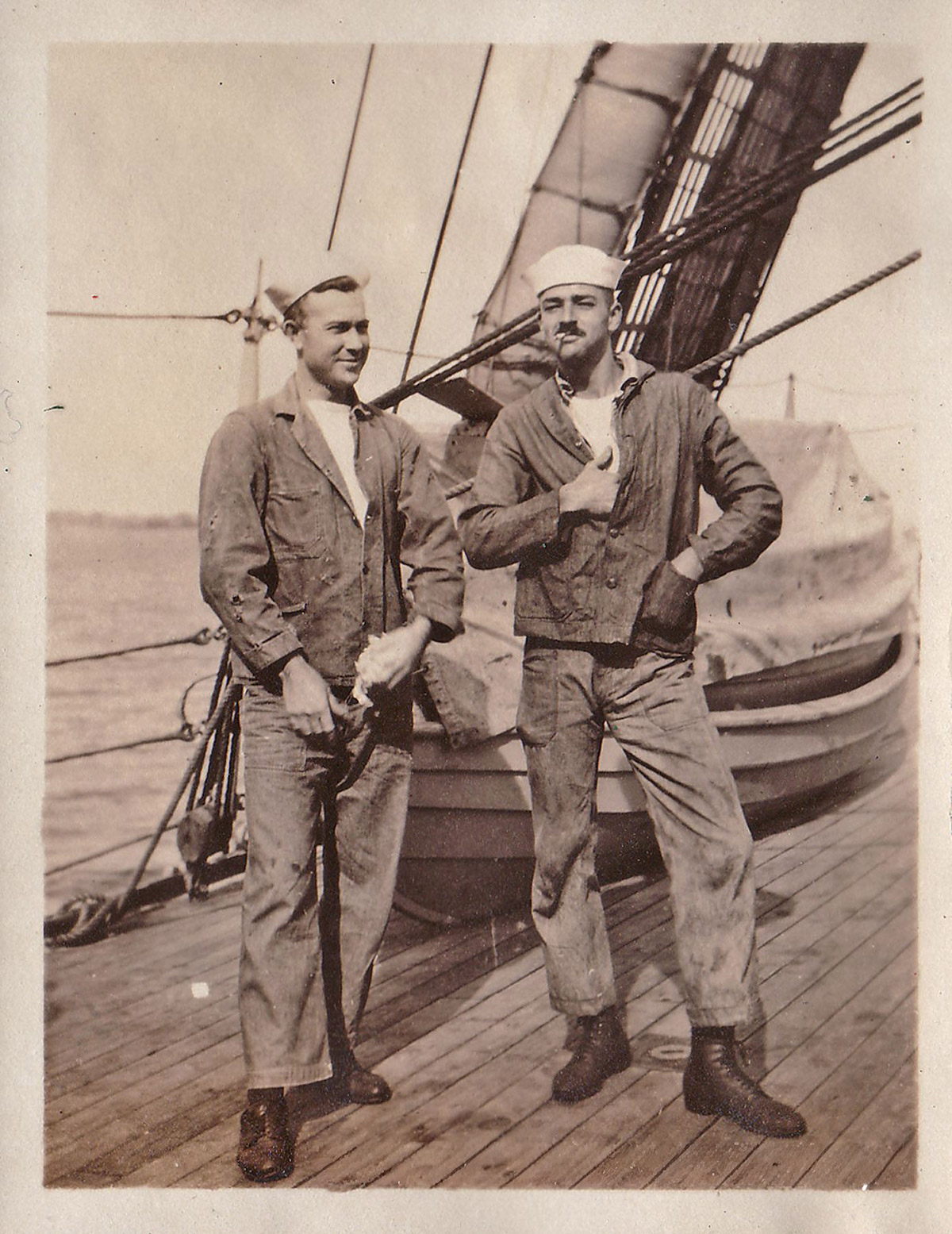

“Jean” originates from “Gênes,” the French name for Genoa, Italy. As early as the 16th century, Genoa was famed for producing a sturdy fustian textile—a blend of cotton, often with linen or wool, similar in texture to corduroy. This durable, affordable fabric was ideal for the working class. The Genoese navy famously equipped its sailors with trousers made from the material, as it could withstand the harsh realities of life at sea. The characteristic blue color came from indigo dye, which became accessible for the working classes after Vasco da Gama opened new trade routes to India in the late 15th century.

Meanwhile, in the late 17th century, weavers in Nîmes, France, were attempting to replicate the popular Genoese fabric. In the process, they accidentally created something different and more robust: a unique, high-quality cotton twill known as “serge de Nîmes,” eventually shortened to “denim.”

The crucial distinction was in the weave. While Genoese jean was woven from two threads of the same color, denim was a warp-faced twill constructed with an indigo-dyed warp thread passing over undyed white weft threads. This technique produced the fabric’s signature diagonal ribbing and its characteristic two-toned appearance—blue on the outside, white on the interior.

The modern garment is a convergence: an American invention made from the superior French fabric, denim, which ultimately adopted the name of its Italian predecessor, jean.

An American Innovation: Patent No. 139,121

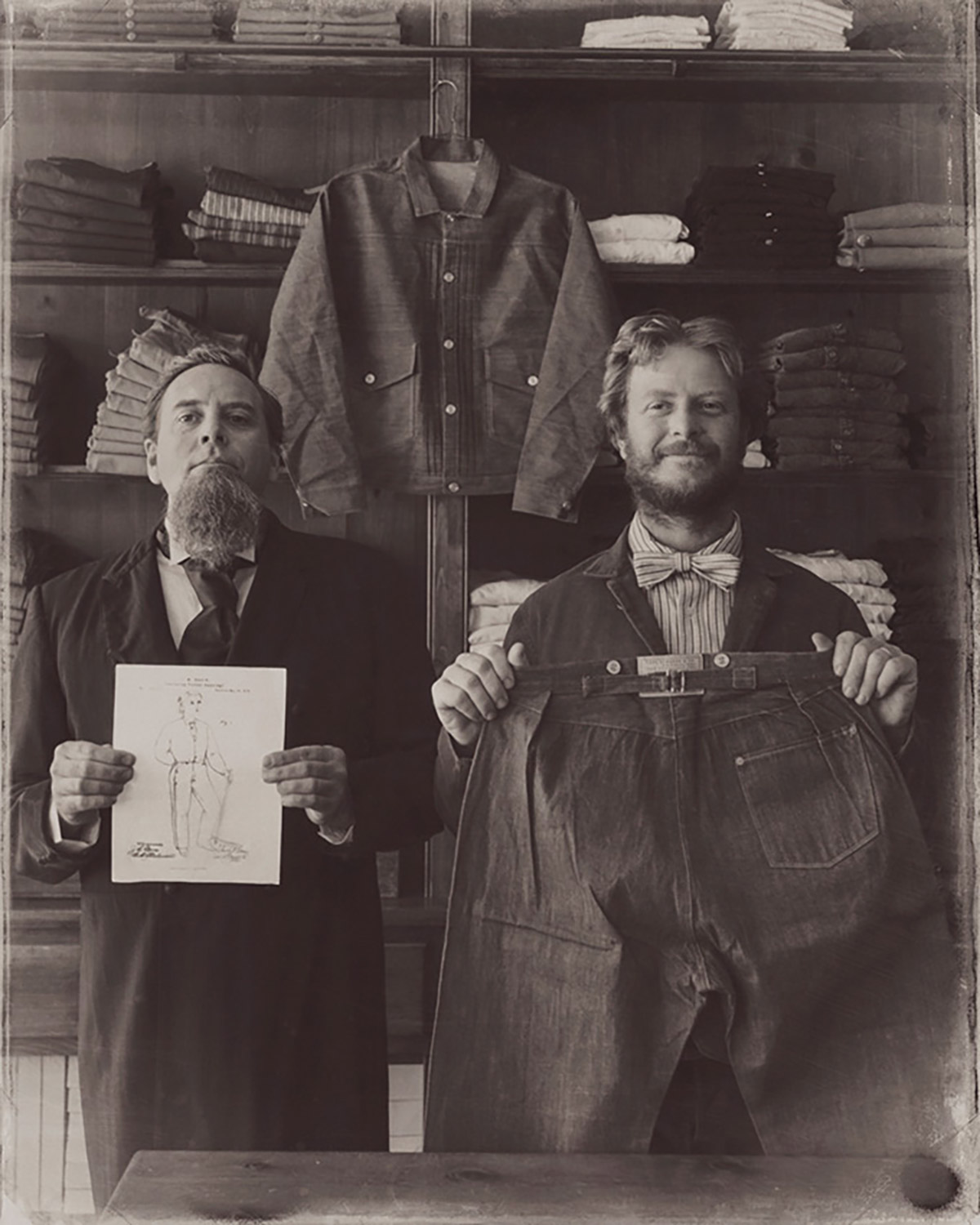

The modern blue jean was not conceived in a fashion house but forged in the demanding environment of the American West. The California Gold Rush of the mid-19th century created a massive market of miners and laborers in desperate need of pants that could endure punishing wear. Levi Strauss, a Bavarian immigrant who established a wholesale dry goods business in San Francisco in 1853, supplied essentials, including bolts of denim, to these burgeoning communities.

The critical innovation, however, came from one of Strauss’s customers, a tailor in Reno, Nevada, named Jacob Davis. In 1872, Davis was asked to create a pair of pants for a local woodcutter that would not fall apart at the seams. His solution was structural, not stylistic: he placed small metal rivets at the points of greatest strain, such as the pocket corners and the base of the button fly.

The riveted pants were an immediate and overwhelming success. Recognizing the commercial potential but lacking the funds for a patent, Davis wrote to Strauss, proposing a partnership. On May 20, 1873, the two men were granted U.S. Patent No. 139,121 for an “Improvement in Fastening Pocket-Openings.” This date marks the official “birthday” of the blue jean. The garment, initially marketed as “waist overalls”—a name that persisted until the 1960s—was born not from a desire for a new look, but as a pragmatic engineering solution to a mechanical problem.

The Myth of the West and the Rise of the Rebel

The riveted “waist overalls” quickly became the indispensable uniform for the miners, loggers, farmers, and railroad workers building America. Among the most loyal early adopters were cowboys, whose physically demanding lifestyle made the tough pants ideal for long hours in the saddle.

In the 1930s, this association was strategically harnessed by marketers and romanticized by Hollywood. Westerns became the dominant film genre, and actors like John Wayne, famously wearing cuffed Levi’s 501s in the 1939 film Stagecoach, projected a powerful image of rugged American masculinity. The jean-clad cowboy became a mythic figure, a symbol of independence and the untamed frontier. Simultaneously, the “dude ranch” phenomenon saw wealthy East Coast tourists adopting jeans as leisurewear. A 1935 Vogue article even advised readers on the proper “uniform for a dude ranch,” detaching the garment from its purely working-class origins.

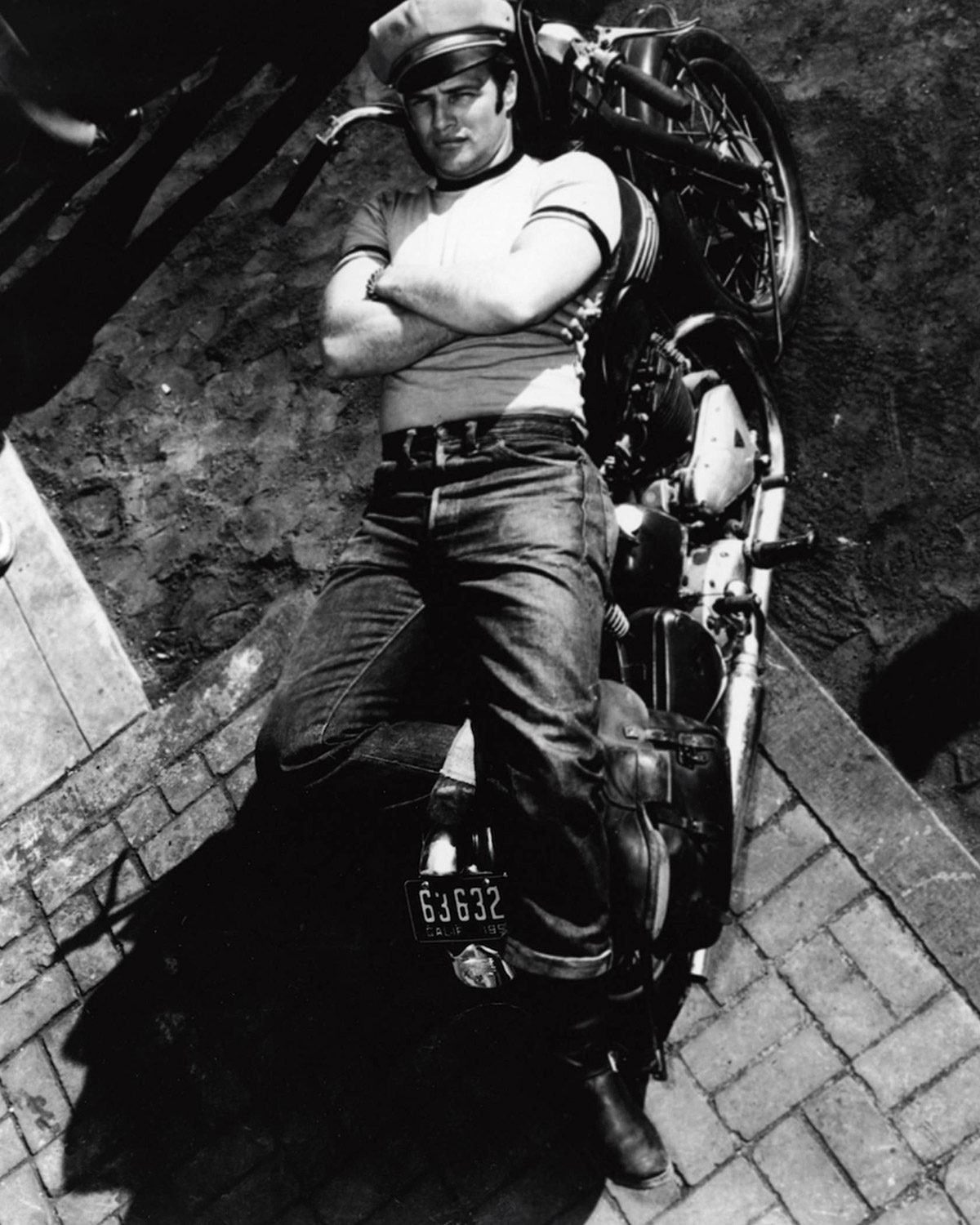

This romanticized image of authenticity paved the way for the garment’s next profound transformation. In the post-World War II boom, a new demographic—the “teenager”—sought a uniform to express their distinct identity. They found it in denim.

Marlon Brando in The Wild One (1953) and James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) cemented the look of the anti-authoritarian rebel: jeans, a white T-shirt, and a jacket.

Simultaneously, denim was being redefined for women. While women had worn jeans for labor during the war years, Hollywood stars like Marilyn Monroe popularized them as fashionable leisurewear. Her appearance in films such as River of No Return (1954) and The Misfits (1961) infused the rugged textile with a potent dose of glamour and sex appeal. Monroe demonstrated that denim could be both rugged and intensely feminine, normalizing jeans as casual wear for a generation of women.

Teenagers across the country adopted the look as a potent symbol of defiance against conservative norms. Fearing the association with delinquency, high schools and theaters banned jeans outright. Paradoxically, this prohibition only validated their power as a counter-cultural symbol. The official disapproval was the ultimate endorsement.

The Fabric of Protest: Solidarity, Subversion, and the 1960s

In the tumultuous 1960s, the symbolism of the blue jean deepened and fractured, moving beyond the generalized teenage rebellion of the previous decade. The garment became central to the era’s major social and political upheavals, utilized in distinct ways by the Civil Rights Movement and the burgeoning hippie culture. Both drew power from the jean’s authentic, working-class roots, but interpreted that authenticity in vastly different ways.

For the Civil Rights Movement, the adoption of denim was not a fashion trend; it was a calculated, visceral, and often dangerous political strategy. In the early years of the movement, activists often adhered to “respectability politics,” wearing their “Sunday Best”—suits, ties, and dresses—during protests. This was a conscious effort to command dignity and counter racist caricatures. However, as the movement intensified and focused on voter registration in the rural South, this dress code became a barrier.

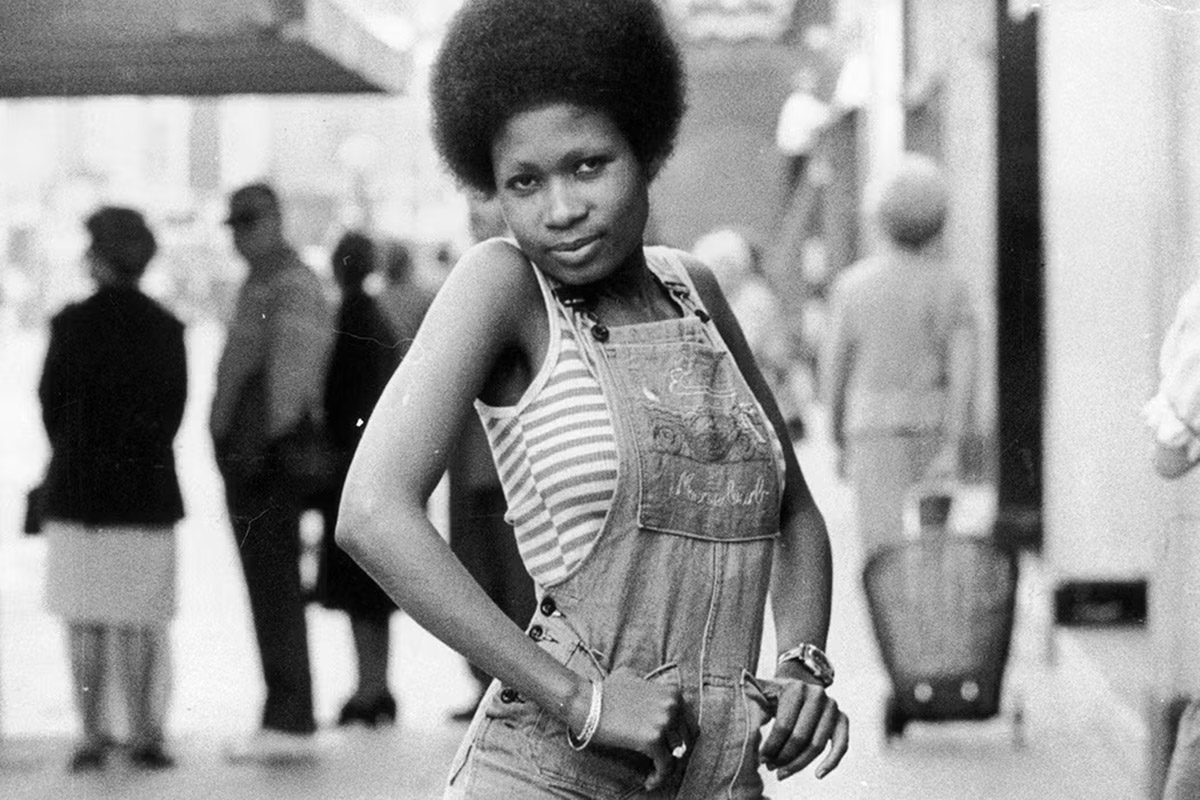

The young activists of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) were among the first to radically change the uniform. They began wearing blue denim overalls and jeans, the daily attire of the Black sharecroppers they were organizing. This was a profound act of solidarity, visually bridging the gap between the organizers and the communities they served. By wearing the uniform of the agricultural laborer, SNCC activists signaled that the fight for civil rights was inextricably linked to the fight for economic justice.

Furthermore, this choice was a potent act of historical reclamation. The coarse, durable fabrics used for workwear had long been associated with the clothing worn by enslaved populations and, later, by sharecroppers. By consciously wearing the fabric historically linked to their oppression, Civil Rights activists transformed it into a symbol of pride, resistance, and liberation. In the deeply segregated South, where strict sartorial hierarchies were enforced, wearing the clothes of the field in the streets of the city was a direct challenge to the established racial and economic order.

The visual impact of this movement was striking. At the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, while the speakers on the podium were largely in suits, the crowd included a sea of denim overalls, signaling that the movement was rooted in the economic struggles of the working class.

Perhaps the most iconic endorsement of this uniform came from the leadership. During the pivotal 1963 Birmingham campaign, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rev. Ralph Abernathy were famously arrested while wearing matching denim work jeans and shirts. The image of Dr. King—the movement’s most recognizable and formally dressed leader—imprisoned in the clothing of a laborer resonated globally, powerfully illustrating the intersection of racial oppression and economic exploitation.

Simultaneously, the predominantly white anti-war and hippie movements embraced jeans for different, though related, reasons. For them, denim’s working-class connotations represented a rejection of bourgeois materialism and conformity. If the Civil Rights Movement used denim to emphasize the group and its shared history of struggle, the hippies used it to emphasize the self and its unique creativity.

From Counter-Culture to Couture: The Designer Era

If the 1960s introduced new silhouettes, the 1970s saw them explode into the mainstream. The bell-bottom, once a radical statement, became the defining fashion of the decade. Popularized by icons like Sonny and Cher on television, the style became the de facto uniform of the disco era. By the mid-1970s, jeans were no longer a controversial symbol but a universally accepted garment.

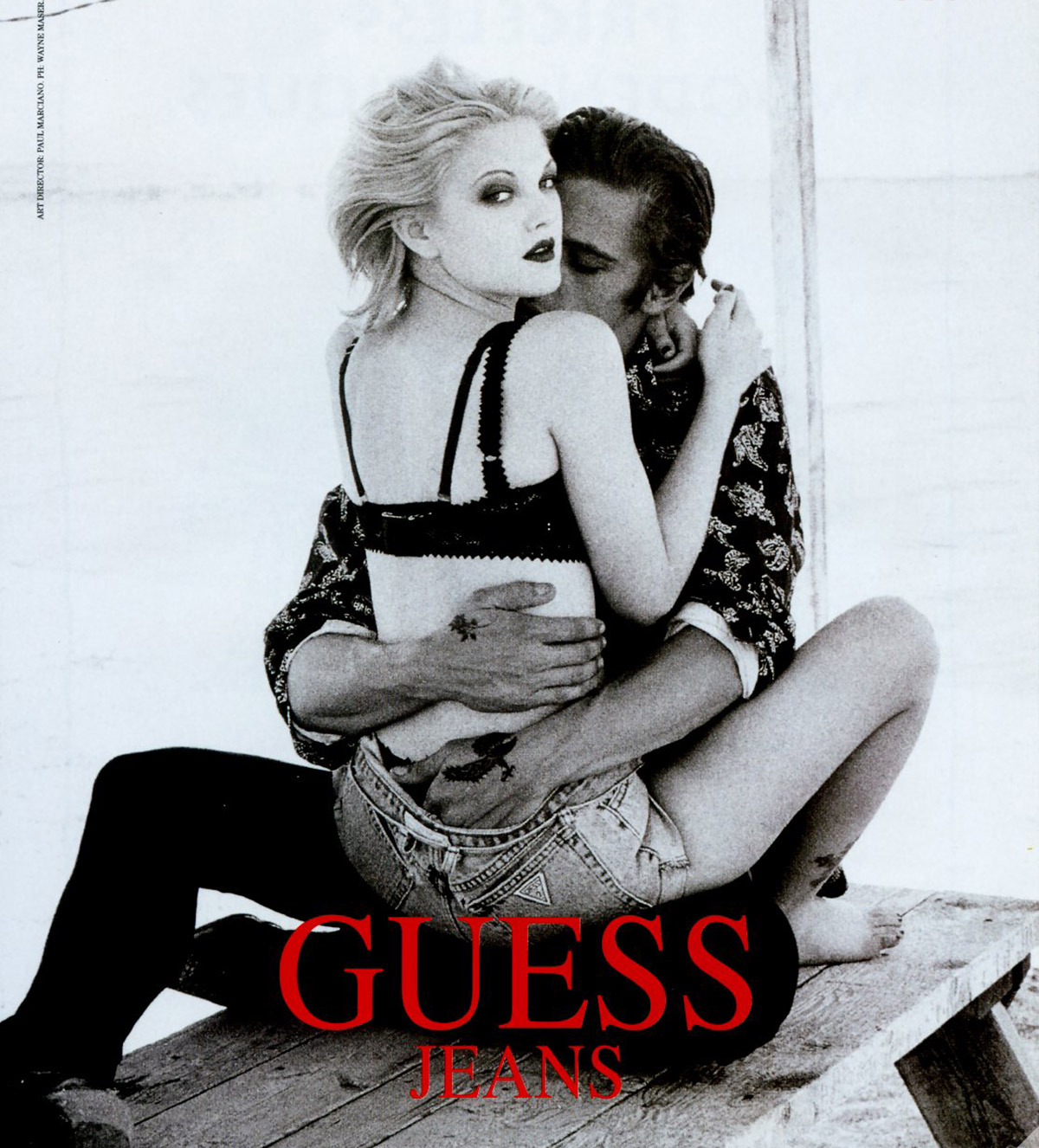

The late 1970s and 1980s witnessed the most radical reinvention of the blue jean: its transformation from a democratic, utilitarian garment into a high-priced, exclusive status symbol. This shift began with European brands like Fiorucci, but exploded in the United States with the launch of Gloria Vanderbilt jeans in 1976.

Vanderbilt, teaming up with manufacturer Mohan Murjani, created the first line of designer jeans for women. The innovations were twofold: a focus on a tight, flattering fit, and the pioneering placement of her signature on the back pocket. This act of branding transformed the garment into an aspirational item.

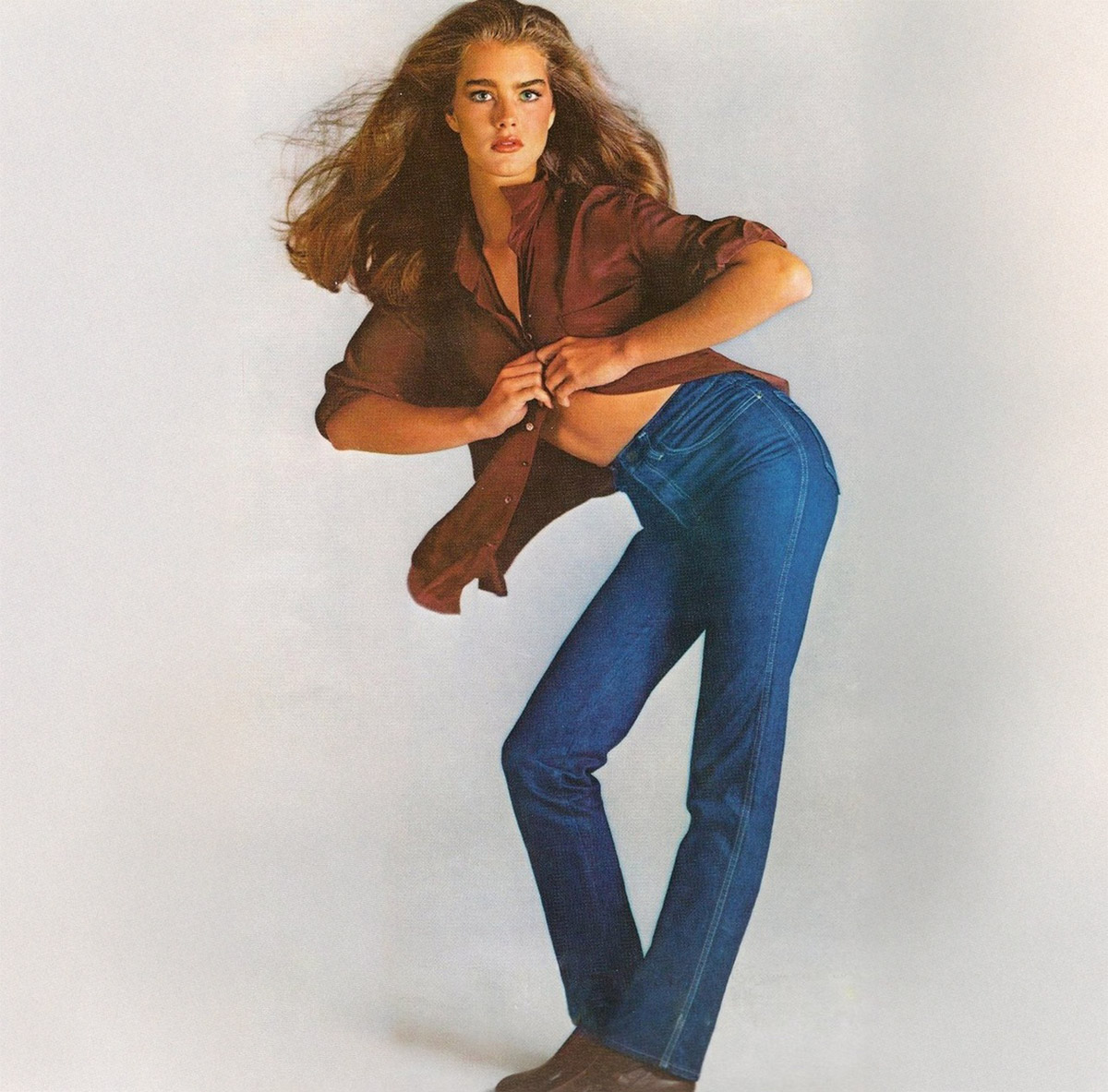

Calvin Klein followed, propelled by revolutionary and highly controversial advertising. The infamous 1980 campaign, shot by Richard Avedon, featured a 15-year-old Brooke Shields provocatively uttering the line, “You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins? Nothing.” The ads caused a public uproar and were banned by major networks, but the scandal only fueled demand.

This phenomenon represented a complete inversion of the jean’s original meaning. A product rooted in working-class authenticity and durability was remade into a luxury good whose value was derived entirely from a designer logo and its association with sex, glamour, and social status.

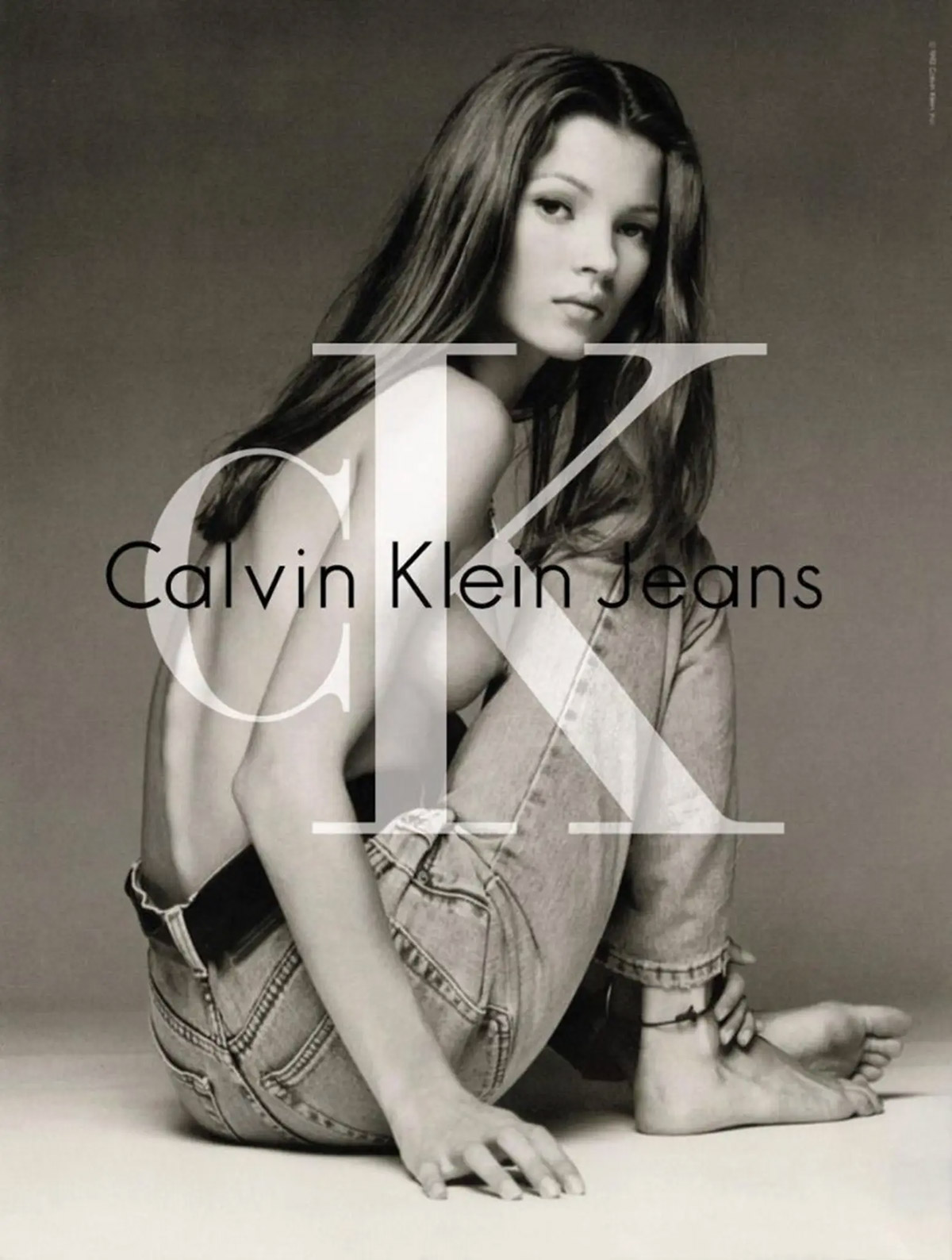

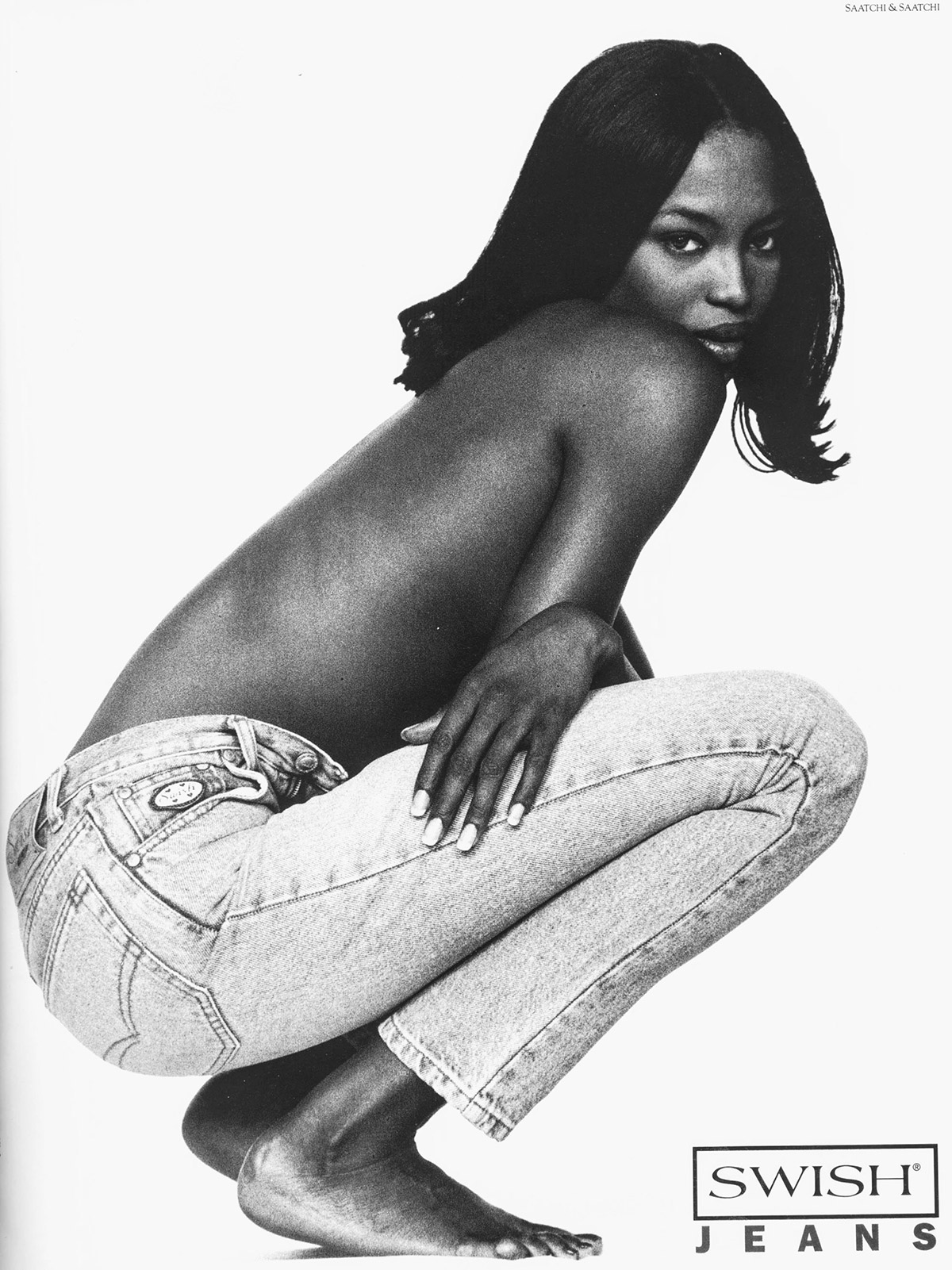

The 1990s solidified denim’s luxury status, driven by iconic advertising campaigns that defined the decade’s aesthetics and often overshadowed the clothing itself. The era was marked by contrasts. Calvin Klein championed a minimalist, grungy aesthetic, launching Kate Moss to international fame in 1992 with controversial ads that defined the “waif” look.

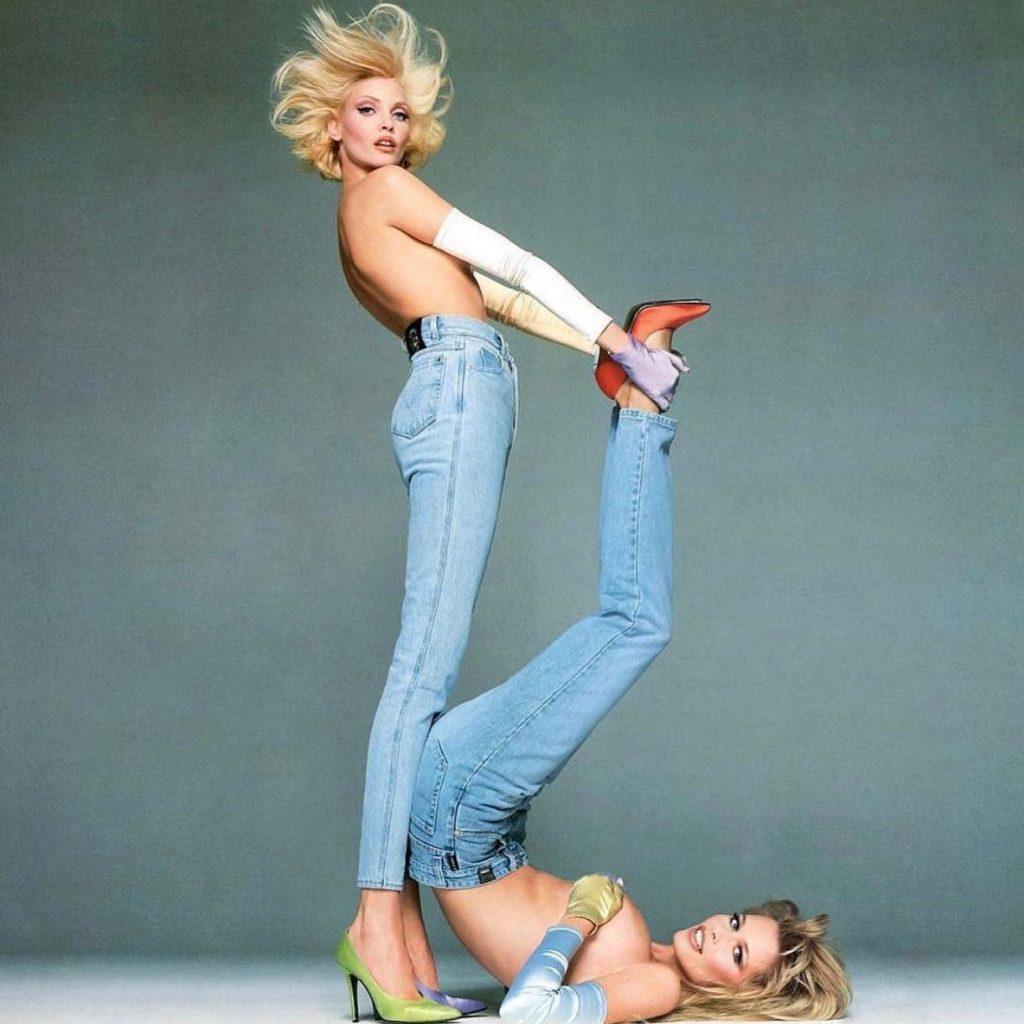

Simultaneously, fashion houses embraced extravagance; Versace Jeans Couture utilized the power of the supermodels.

Naomi Campbell, who also fronted provocative campaigns for brands like Swish Jeans.

The Industrialization of Authenticity

Concurrent with the rise of designer jeans were technological innovations that allowed for the mass production of the “worn-in” aesthetic—the very essence of vintage denim. This development marked the final separation of the jean’s look from its history of authentic use.

Techniques like stone washing, popularized in the 1980s, involved tumbling finished garments with pumice stones to scrape away the indigo dye and soften the fabric. An even more dramatic technique, acid washing, emerged from this. The process, industrialized and patented by the Italian firm Rifle Jeans in 1986, used bleach-soaked stones to create a stark, mottled blue-and-white contrast.

These techniques allowed consumers to purchase the look of a lived experience without having to live it. The fade, once a testament to a personal history of labor or rebellion, could now be chemically and mechanically engineered in a factory.

The history of denim is a remarkable narrative of transformation and reinterpretation. No other garment has demonstrated such a unique capacity for reinvention. The blue jean has been, and continues to be, a symbol of the laborer, the cowboy, the rebel, the activist, the rock star, and the fashion elite—often all at the same time. Its journey from a simple pair of sturdy trousers to a global cultural canvas makes it the most potent and enduring garment of the modern world.